Digital IDs in a digital society

Joseph Carson at Delinea argues that digital IDs pave the way to a digital society – but only if governments can be trusted to provide citizen services ethically and transparently

As our lives become increasingly digitised, some may argue that the UK’s public infrastructure is failing to keep up. One of the most vocal arguments came recently from former Prime Minister Sir Tony Blair and Conservative leader Lord William Hague. The one-time political opponents have united in calling for a "technological revolution" by introducing digital IDs for everyone in the UK.

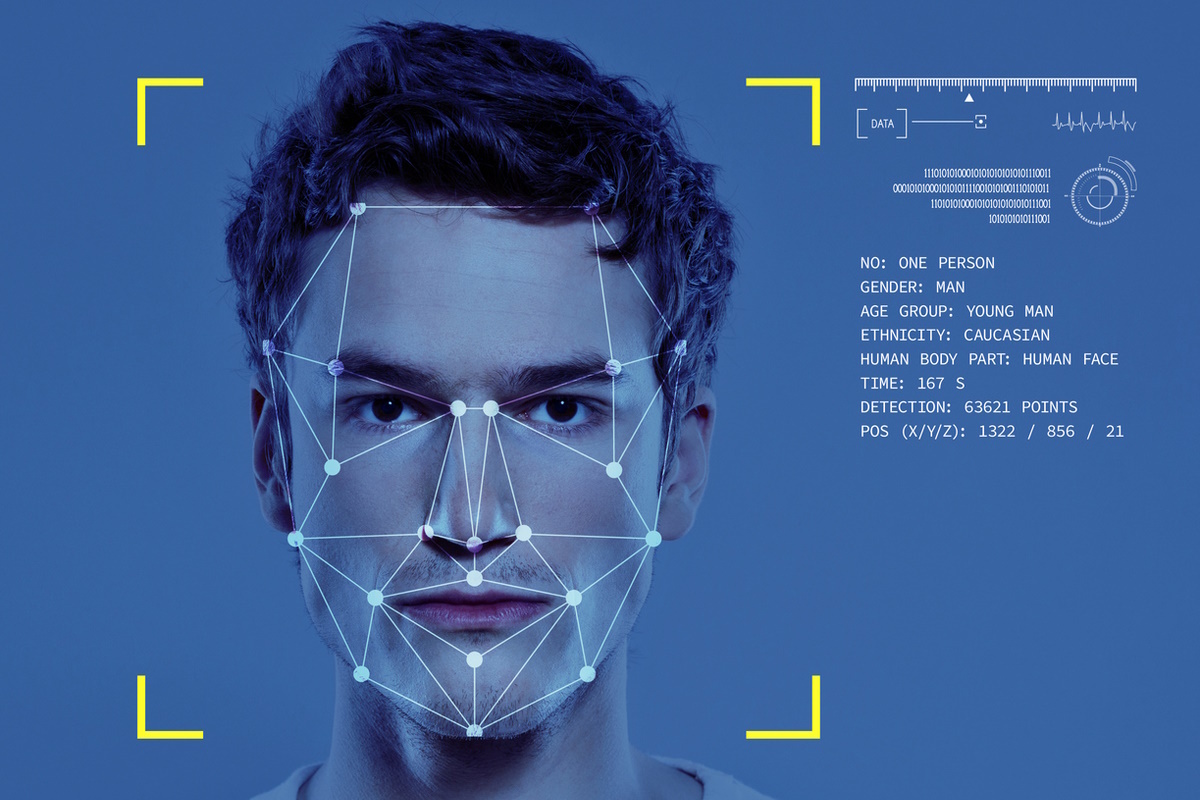

A report published in February argues that public records need to align with the fact that most other aspects of our lives, from banking to international travel to vaccine status, are handled on our devices. The proposed scheme would include identity, age, driving license, right to work, and other factors in a single digital ID and digital wallet, making accessing services easier.

However, digital IDs have proved controversial, with critics warning that they can invade privacy and that identities will be at increased risk. Notably, the UK government’s Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology (DSIT) has issued a report on digital identity. Yet, execution of this programme has stopped short.

Implementing digital identities is the first step toward a truly digital society. There have been many examples of this system working to better the lives of everyone, as seen with success stories in other countries, including Estonia, my country of residence.

However, digital identities are a complex matter, where significant security and privacy checks must be in place for the switch to succeed. Governments must build trust and it is critical to provide transparency to the citizens on usage of their data.

Digital identities demand trust

Having introduced its digital identity system more than 20 years ago, Estonia has long been a frontrunner in the move toward a digital society. It is therefore held as a model of what can be achieved.

Rather than wasting time standing in lines, citizens can access all manners of government services, everything from education to taxes, health to finance, and everything in between, through their devices, from any location. In 2005, Estonia became the first country to hold a legally-binding, online election.

Although, reaching this point was no simple task. First and foremost, digital identity must always serve as a front door to government services for the citizens - not a backdoor for the government to access their data. Giving the citizens the ability to audit the government’s use of their data, and hold them accountable, is a cornerstone of successful digital identity.

Furthermore, a digital identity programme must be built on a solid sense of trust. As in any other context, this trust cannot be assumed; it must be earned over time. Citizens need to be confident that their personal information will be safeguarded within a secure, transparent system.

When a government adopts a digital identity for government services, it ought to realise that they are becoming a service provider, and the citizens are the ones in control. The government’s intent as well as its technical ability to live up to this role are crucial; putting the citizens’ needs first and protecting their information with high assurance.

Cyber-threats and security implications of digital IDs

All digitisation comes with increased cyber-risk, and governments initiating digital IDs must be cyber-ready. Having the correct checks and balances in place is the only way to ensure success.

A single, online system hosting such a vast amount of personal data, becomes a natural target for cyber-criminals seeking to commit identity theft and financial fraud. Digital public services are also vulnerable to disruption from ransomware. Indeed, the FBI recently reported that government facilities are the third most targeted sector for ransomware attacks, only behind critical manufacturing and public healthcare.

Digital identity infrastructure is another obvious target for nation-state-level actors. A prominent example came in 2007, when Estonia was targeted by a series of cyber-warfare attacks that targetted the country’s digital society. These cyber-incidents were in response to a dispute about relocating the famous Bronze Soldier of Tallinn grave marker, the campaign included Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, targeting governmental services and leading banks.

Securing digital identities against any threat

Digital identity schemes need to be protected by the very best cyber-security practices. Technologies, such as Privileged Access Management (PAM) and multifactor authentication (MFA), are essential for protecting identities against threat actors.

While cyber-security is the obvious priority, safeguarding a national digital identity system presents a physical challenge. If something happens to the data centre hosting the information - either through a physical act of war, sabotage, or simply a natural disaster – there is a risk of the information being lost. This is a catastrophic outcome for a digital society, so a contingency plan must be implemented.

In Estonia, the cyber-threat led to the idea of decentralisation. Rather than being limited to data centres within the country, identity data is decentralised to reduce the risks. Since the data must legally remain within a sovereign territory, the initial plan for Estonia was to create data embassies. This scheme has since progressed, with the first new data centre opening in Luxembourg in 2015.

As our societies continue to digitise rapidly, digital ID plans, like that proposed by Blair and Hague, make perfect sense to ensure the public sector keeps up. A universal digital identity can bring wide-ranging benefits, saving valuable time with an accessible, centralised system for all essential needs.

In addition, allowing for automation, that will buy back even more time for citizens and governmental bodies alike, for example, using AI to fill in forms and requiring only authorisation. Time saved is the ultimate metric for success in a digital society. The most valuable resource in the world is time and we must make the most value out of it as possible.

Alongside security, however, the most crucial aspect of digital identity is a sense of transparency and trust between citizens and authorities. The focus must always be on the value for the people, not the government.

Joseph Carson is Chief Security Scientist and Advisory CISO at Delinea

Main image courtesy of iStockPhoto.com

Business Reporter Team

Most Viewed

Winston House, 3rd Floor, Units 306-309, 2-4 Dollis Park, London, N3 1HF

23-29 Hendon Lane, London, N3 1RT

020 8349 4363

© 2025, Lyonsdown Limited. Business Reporter® is a registered trademark of Lyonsdown Ltd. VAT registration number: 830519543