American View: How Does Your Organisation Mitigate the Likely Consequences of Employees’ Irrational Beliefs?

People are weird. That’s what makes my job as a “human risk” specialist so fascinating. No matter how much I learn about cognitive science, psychology, sociology, and aberrant behaviour, I’m regularly amazed at people’s bizarre conduct and the insanely twisted logic they offer to retroactively justify it. “You did what to who because why, Bob? Really?!”

Often, such weirdness is harmless and might even be socially acceptable. If someone wants to hoard frozen dinners and bog roll “preparing” for an imminent alien invasion, their irrational purchases aren’t actively harming anyone. Here in the USA, most folks on the left and right wings of the political spectrum take the view that every adult should be free to believe any danged thing they want so long as they don’t cause trouble for others. This obviously takes wildly different forms between the left and right; if a California “new age” acolyte wants to treat her COVID infection with “crystal energy” that’s effectively the same decision as her “bro country” farmer cousin in Kentucky treating his COVID infection with veterinary parasite cream. The public take usually boils down to “Y’all are probably gonna die for ignoring medical science and common sense, but … whatever. It’s your life. Have fun.”

To a large extent, that populist “live and let die” philosophy allows a nation chock full of irrational folks to get along reasonably well. That attitude extends to the workplace: corporate Human Resources types are usually loathe to say anything about (let alone to condemn!) a worker’s personal beliefs and practices so long as they don’t interfere with production or contribute to a hostile work environment. “Aliens? Cool, Bob. Are your slides ready?”

I’m not opposed to this. I don’t want to be discriminated against or harassed and figure most everyone else feels the same. We just want to live our weird little lives free from interference. Nonetheless, people’s irrational beliefs play a significant part in forming their worldviews, which in turn affect how they rationalize what constitutes acceptable behaviour in the workplace … like whether to follow or violate mandatory security controls. That’s where it becomes my problem.

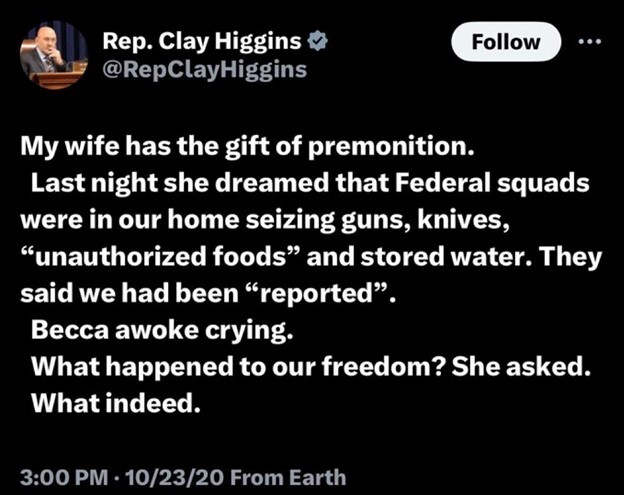

I got to thinking about this last week while doomscrolling Twitter. [1] One of the luminaries of Military Twitter -- @CombatCavScout – derisively shared this baffling three-year-old tweet from Louisiana congress critter Clay Higgins [2]:

I stopped mid scroll and tried to wrap my head around such a ludicrous claim.

I'm fascinated by this "unauthorized foods" premonition. WTAF? Did she imagine a SWAT team kicking in the door while screaming at her to drop the snack foods while her jackwagon hubby screamed "You can take our guns, but you'll never take our Cheetos!"

— Keil Hubert (@KeilHubert) January 12, 2024

“I’m fascinated by this ‘unauthorized foods’ premonition. … Did she imagine a SWAT team kicking in the door while screaming at her to drop the snack foods while her jackwagon hubby screamed ‘You can take our guns, but you’ll never take our Cheetos!®’”

It seems that I mistook the congress critter’s comments as nothing more than the usual apocalyptic bloviation that defines the fringe elements of his political party. A polite tweeter pointed out that I must have missed one of the fake “culture war” wedge issues: Rep Higgins’s party has been vociferously campaigning to end legal prohibitions against selling unpasteurized milk for human consumption. This dangerous anti-science campaign has been a winning issue for politicians who claim that “too much regulation” is somehow “anti-American” … such a stance plays well to the average voter on both sides of the political divide who believes that they should be allowed to do anything they want so long as they’re not hurting anyone else.

I get the angle. Sure, this dubious practice exposes consumers to much higher risk of serious injury, however – our right-wing politicians claim – it’s not a “health and safety” issue but a “personal choice” issue … using much of the same language and logic that our left wing politicians used to advocate for drug legalization. Claiming that you’re “freeing” the common person from intrusive government overreach is 100% American. It sells.

In both cases, though, the “personal choice” angle glosses over the downstream effects these “beliefs” can have on others when acted upon. In the Sentinel Echo article that I linked above, journo Tony Keys related the story of Mary McGonigle-Martin, a member of the food-safety group Stop Foodborne Illness. As he explained:

“McGonigle-Martin … testified four times over several years against legalization proposals in the Iowa Legislature. She recounted how her son, Chris, became critically ill after drinking raw milk tainted with E. coli in 2006.

“McGonigle-Martin said in a recent interview that she bought the milk at a health food store because she hoped a natural diet would help her son, who had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. But Chris, who was 7, became severely ill less than three weeks after starting to drink it.

“He spent two months in the hospital, and doctors had to put him on a ventilator and kidney dialysis while his body fought off toxins produced by the bacteria.”

I reckon you could change out the text “drinking raw milk” with “gargling industrial acid” and the story would end roughly the same. Ingesting something proven to be hazardous in the hopes that it’s both (a) not hazardous and (b) somehow beneficial stretches the “freedom of choice” into suicidal irrationality.

That’s where the “let me do whatever I want” arguments tries to align with drug legalization arguments: advocates argue that an individual should be allowed – in accordance with general sentiment – to risk harming themselves at their own risk. To wit, “if I burn my brain out on LSD, I’m the only one harmed by it.” That appeals to the surly individualist spirit of the average American. I get it … except that it misses the point. What one chooses to do to oneself can still negatively impact others.

To be fair, some irrational beliefs are generally harmless; believing that shapeshifting lizard people secretly rule the world [3] doesn’t really impede office work. On the other hand, believing that “raw water” has magic healing properties probably will disrupt office work … in that quaffing unfiltered and untreated water chock full of animal faeces, pesticides, and industrial waste will eventually lead to hospitalization and death, two conditions that make it difficult to show up on time for staff meetings.

This is why trying to address human risk often ties organisations in knots. HR and Legal types are – in accordance with their essential nature – perpetually terrified of getting sued. The mere suggestion that a company should dictate to its employees what they can and cannot do outside the office is largely unthinkable. [4] The “you can’t tell me what to do!” crowd won’t stand for it … to be fair, they make an excellent point. If my boss demands that I attend her church on Sundays if I want to stay employed, that’s utterly unacceptable.

A more nuanced approach suggests that the company should know about and, thereby, attempt to actively mitigate key employees’ “high risk” activities. If Liz from Accounting is obsessed with extreme sports that are known to have a 10% fatality rate and she takes four high risk vacations a year to thumb her nose at the gods of fate, doesn’t the company have legitimate reasons to be concerned for its own protection? Liz is gambling with her life; eventually, she’s going to roll snake eyes and croak. Sure, that’s totally her choice and we should all support her hobby, but … does that mean it’s Liz’s employer’s responsibility to hire and maintain a fulltime backup for Liz to minimize the impact of her inevitable plunge off an Alp? How is that more cost-effective than simply placing restrictions on Liz’s extracurricular activities as a condition of employment? Or demanding that she take out a bond before every ice climbing expedition to cover the cost of an emergency consultant if and when she tumbles down a glacier?

I know, I know … “YOU CAN’T DO THAT!!!” I’m not trying to give the lawyers cerebral embolisms here. I’m trying to point out that purely “personal choice” decisions – rational or not – rarely affect just the person making the choice. When the consequences of a worker’s beliefs include illness, disability, or death as possible outcomes, their employer will be affected by that choice … even if the output of the results isn’t communicable. By risking their own health and safety, the employee is unilaterally imposing the consequences of their beliefs on their employer.

On the one hand, that ain’t cool, bud. On the other hand, the same risks factor into nearly every decision a person makes throughout their life. Want to save money commuting by motorcycle instead by car or train? That’s higher risk! Can or should the company declare all morotcycles verboten? Or just “crotch rockers”? should they be acceptable during clement weather only? What if the driver steadfastly refuses to wear a helmet (which is legal here in Texas)?

As said at the beginning, my professional interest in this topic narrowly focuses on how people’s irrational beliefs affect how they rationalize what constitutes acceptable behaviour in the workplace. My job is to encourage compliance – and, by extension, to discourage noncompliance – via effective security requirements and best practices. More of the good stuff, less of the bad.

We last tried having this discourse during the first year of the pandemic when it became clear that an unvaccinated, unrepentantly social individual had a significantly higher probability of not just getting infected but of infecting others … thereby potentially killing off their co-workers. For about 18 months, it was generally accepted that exposing your co-workers to things that might kill them was unacceptable. You’d think this discourse would have encouraged a more thoughtful, wider ranging discussion about similar dangerous behaviours … but no.

That said, I’ve found that some people’s extreme irrational beliefs encourage willful noncompliance as a mitigation tactic. For example, if Liz from Accounting constantly flirts with death-by-Yeti on her holidays and when the company won’t effectively mitigate the probably risk of Liz expiring in a crevasse, it seems reasonable that it’s in Accounting’s rational self-interest to take steps to carry on if/when Liz buys it.

If the company won’t preemptively mitigate the risk, then the workgroup must. This is how we wind up with system backdoors, elevated access permissions for users won’t don’t normally need them, account passwords left on sticky notes, and all the other completely unacceptable security risky behaviours in the office. Except that the expected conditions those security controls were written for probably didn’t account for the increased probability of key personnel buying the farm before their allotted three score and ten. Most policy is written with the assumption that users will be “reasonably” careful and will show up every workday. Odds are, they didn’t consider Liz.

If my “preemptive risk mitigation” reasoning seems far-fetched, and something employer would never consider in the real world, I advise you to check out my book on Hiring Forever War Veterans. From 9/11 through to the withdrawal from Afghanistan, U.S. employers were hesitant to hire American military reservists. As Theodore Finginski wrote in the Harvard Business Review:

“My findings suggest that there is a negative effect associated with current service in the Reserves. Compared with résumés indicating completed Reserve service, résumés indicating current service were 11% less likely to be called for an interview. One explanation is that employers may be weighing the cost of losing a reservist employee to full-time military service for an extended period. They may also be weighing the cost of hiring and training a replacement. For example, what should the employer do when the reservist employee returns — expand the workforce to include both the returning reservist and the replacement, or choose to lose the investment made in the replacement employee? Employers may simply choose to hire fewer reservists to avoid confronting a potential issue like this one.

“… the negative effect associated with current service in the Reserves is likely to be greater for jobs involving specialized skills or requiring significant on-the-job training. Finding temporary employees to replace reservist employees in these jobs is likely more difficult. As a result, employers are unlikely to invest in a temporary employee to cover for the reservist in the event of an absence due to full-time military service, making hiring a reservist in the first place potentially costlier to the employer.”

This is something companies already do. Every squaddie who’s tried to get a corpo job since 2001 knows full well that a hiring manager’s perception of their risk profile reduced their chances of getting hired. Because they chose to enlist during wartime – a seemingly irrational personal choice to many civilians – the perceived downstream risk to the employer was treated seriously and acted on rationally … often to the squaddie’s detriment.

So, let’s skip over the irrelevant “should we consider this” arguments and get straight to the point: where does our organisation draw the line between which risky personal beliefs (and subsequent risky behaviours) we’re willing to mitigate and which we’re comfortable ignoring? Where’s the cut-off? And how far if your organization willing to go to blunt the impact of a worst-case scenario? Where does Liz from Accounting fall on the spectrum? And what are we gonna do about her?

[1] Rep Higgins’ job title isn’t meant personally; I find that most of our elected representatives are amoral, corrupt, reprehensible, lying jack wagons.

[2] Twitter is still Twitter; calling it “X” just feeds a spoiled tech bro’s already distended ego.

[3] As approximately 4% of Americans seem to believe.

[4] Which is hilarious given how long it’s been normal for employers to fire workers for their off duty drug use.

Keil Hubert

You may also like

Most Viewed

Winston House, 3rd Floor, Units 306-309, 2-4 Dollis Park, London, N3 1HF

23-29 Hendon Lane, London, N3 1RT

020 8349 4363

© 2025, Lyonsdown Limited. Business Reporter® is a registered trademark of Lyonsdown Ltd. VAT registration number: 830519543