American View: When Is It Appropriate to Insult Your Audience?

Mass communications activities for a security awareness team resemble marketing more than anything else. Your mission is to capture your audience’s attention long enough to deliver a message that your users will understand, agree with, and act on.

This mission requires rhetorical finesse, since most of the things we want our people to know, do, or not do require them to change their existing, vulnerable behaviour. It’s a challenge.

This isn’t to say that marketing is horrendously complicated or that practitioners of the Mad Men art are as nervous about their work as we are in the security world.

Traditional marketeers are trying to get strangers to buy a product or service; if their messages fail, they get to try again … infinite times, in most cases. Security professionals, on the other hand, risk enabling a catastrophic cyber-attack if we botch our communications.

That’s usually not a downside risk for the average advert artist ... When they do their job well, they burnish their (or their client’s) brand. Entice new customers. Build loyalty. Maybe gain some credibility with the internet-savvy youth demographic. When they do it poorly, the most that happens is usually some scorn from the public and maybe lost sales to better brands.

There are, however, those mass communications efforts that fail so badly that a brand takes long-term damage to its reputation that might take years or decades to rebuild. Consider the astonishing gaffe JPMorgan Chase bank’s social media team made back on Monday, 20th April 2019. If you missed it, some anonymous “brand ambassador” at the bank (or perhaps at one of its contractors) wrote the following “humorous” exchange on Twitter:

You: why is my bank balance so low

Bank account: make coffee at home

Bank account: eat the food that’s already in the fridge

Bank account: you don’t need a cab it’s only three blocks

You: I guess we’ll never know

Bank account: seriously?

#MondayMotivation

Motivation, yes. Surely. Not motivation to cut down on nonessential spending, but instead to invest heavily in torches and pitchforks. People were (rightly) indignant at the victim-blaming condescension expressed in this tweet. I can’t rightly blame them!

This idiotic take was the textual equivalent of a political cartoon showing a tuxedoed millionaire stepping over a homeless person while sneering “get a job, ya bum!” If the tweeter’s intent was to amuse and/or inspire, they missed the mark. Badly. This wasn’t an ”own-goal;” it was the mass communications equivalent of forfeiting the game at the coin toss.

In response to the tweet, BoingBoing’s Cory Doctorow quipped: “… this doesn’t explain how Chase’s balance reached $12,000,000,000 in the red (perhaps they ate a lot of takeout?), nor does it take account of factors like wage stagnation, increasing inequality, skyrocketing rents, unsustainable student debt, and other structural factors that have put most Americans just one missed paycheck or unexpected hospitalization away from real financial hardship.”

Similarly, Time editor Anand Giridharadas commented: “This is the ideology of our age captured in a single tweet. Systemic problems recast as individual problems. Corporate greed recast as personal failure. A bank claiming to ‘motivate’ its customers by mocking them for structural economic problems the bank is complicit in causing.”

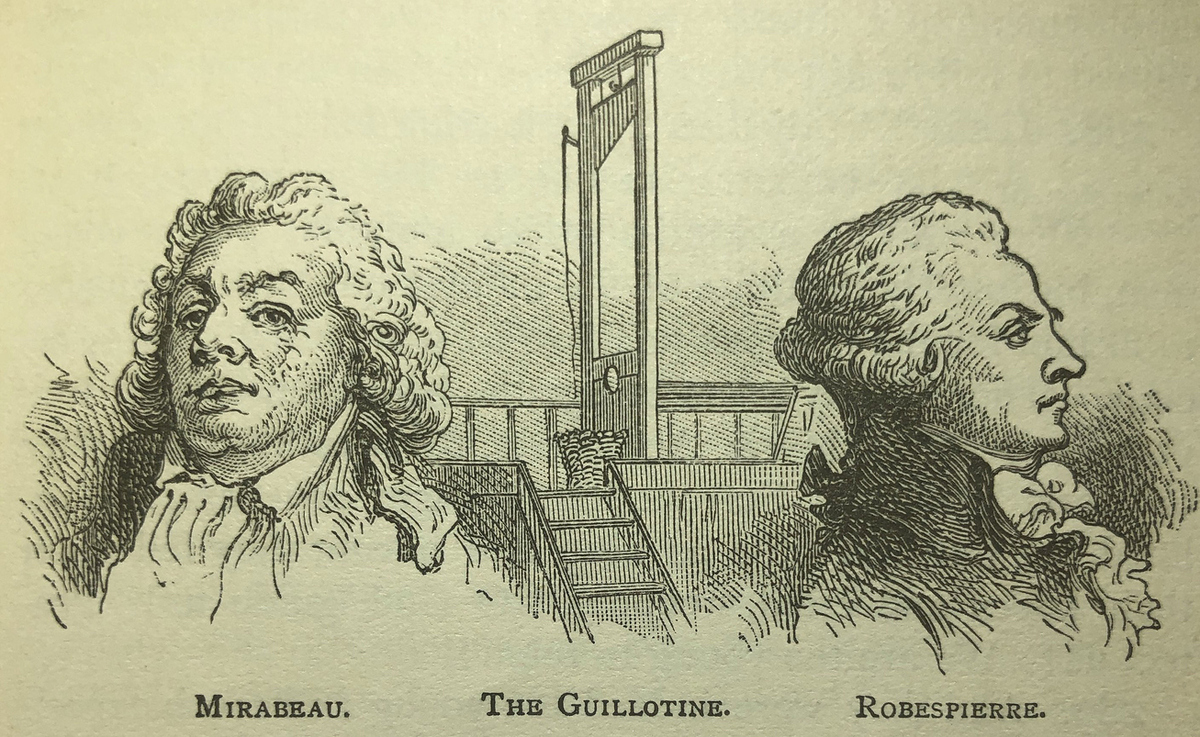

For months after this self-inflicted brand wound, I saw snarky Twitter users posting “response” tweets aimed back at Chase that went something like this:

Chase Customer: why are you so arrogant yet so rich?

Chase Executive: because I’m better than you, filthy peasant!

Chase Customer, smiling: there’s a cure for that!

Animated Cartoon Guillotine: ready when you are, buddy!

#MondayDecapitation

I empathize with the millions of customers who were enraged at Chase’s casual contempt. I can also empathize with the poor writer who misjudged that throwaway joke’s impact and probably cleaned out their desk on 21st April. It’s darned difficult to do comedy, especially when your remit requires you to be hip, edgy, or provocative. Attempting comedy on social media amplifies the risk of a joke bombing; a particularly egregious gaffe can quickly gain worldwide attention and trigger the “pile-on effect” … especially when the failed joker represents a powerful entity ”punching down” on the defenceless, exploited poor.

This tweet (quickly deleted) prompted U.S. Senator (and then presidential candidate) Elizabeth Warren to ask Chase’s CEO to personally apologize. Shortly thereafter (as reported in the Washington Post), U.S. Representative Katie Porter suggested that the view expressed in the tweet was so egregious that the CEO ought to retire because “an apology won’t cut it.” Ouch!

This ought to slay and bury the old aphorism that “all publicity is good publicity.” The blowback from this tweet surely left a stain on the brand. But … should it have?

The structure of the joke itself was fine. The intent of the joke wasn’t inherently offensive; thriftiness is a virtue straight out of the Bible and the Boy Scout Handbook. It was the joke’s blame-the-victim tone that aggravated the zeitgeist. The message that came through was “If you’re struggling financially, it’s because you’re stupid and you make poor decisions. Your poverty is your own fault, and we’re smugly looking down on you.” That’s … provocative. Daring. Offensive, to be sure. Maybe that wasn’t how it was intended, but it’s sure-as-blazes how the Internet reacted to it.

You’d think that marketing’s “prime directive” would be “never tell your customers that you think they’re idiots.” I did my time as a public affairs officer back during the post-9/11 era, and I learned very quickly to avoid wit and mirth when people’s passions were inflamed. Some jokes that would be perfectly appropriate between friends or in an unofficial setting could take on a completely different weight when coming from an authority figure … especially when people were anxious, afraid, angry, or otherwise agitated.

I had to stand in front of cameras on nationwide television to discuss negligent firearms discharges, suspected anthrax attacks, and horrific airplane crashes. The only time it was appropriate to employ humour was after things had settled down and the audience could benefit from a gentle release of tension. Even then, we never attacked anyone.

From that perspective Chase’s infamous jokey tweet should never have cleared editorial review (or whatever passed for it at the time). A trained Public Relations pro would’ve spiked that joke immediately and used the opportunity to re-train its writer(s). I’d bet twenty quid that there was no evil intent behind the joke. I doubt that the writer was some sneering imperialist looking to antagonize the servant class while cackling and twirling their moustache. That’s just … waaaaaay too cartoon-y for the real world.

It’s a lot more likely that the writer/marketeer was a normal person, not too different from the rest of us. They were under pressure to generate witty, viral content that resonated with Twitter users. They probably misjudged their joke’s tone and made an unintentional mistake. It wouldn’t surprise me if the writer realized their error in the first few minutes after the tweet posted and scrambled to run damage control. These things happen. It could just as well have been your organization’s social media team – or, worse, your security communications team!– making a similar gaffe.

Personally, I think Chase should have owned their mistake immediately. A swift and earnest public apology would have done a lot to minimize the “pile-on effect” ... “We should have caught this before it posted. The writer didn’t realize that the tone was antagonistic, and we apologize. We’ll do better.” That’s it. Acknowledge the mistake respectfully and move on. Honestly, that’s the best that anyone can do. Social media is an endless minefield and we’re all going to set some off. A single bad tweet alone shouldn’t vilify an organization or stir up an angry mob. Not if it’s handled quickly and transparently.

Unfortunately, we usually don’t have the same reputational resilience inside the office. Humour absolutely has its place in security communications. It helps users engage with and remember critical content. It helps dry facts become agreeable and emotionally resonant. It builds morale and strengthens corporate culture … when used appropriately. Your mass comms efforts during an active security incident are never the right time for joking around. Please trust me on this.

More importantly, it’s all too easy for security professionals to grow frustrated with their users’ seemingly self-destructive behaviour … enough to blame their users for their errors. That’s a guaranteed path to the wrong flavour of “zero trust.” NEVER accuse your users of being idiots. It might make you feel smug for a few seconds, but the damage you’re surely inflict on your department can’t be mitigated until long after you’ve been sacked.

Keil Hubert

You may also like

Most Viewed

Winston House, 3rd Floor, Units 306-309, 2-4 Dollis Park, London, N3 1HF

23-29 Hendon Lane, London, N3 1RT

020 8349 4363

© 2025, Lyonsdown Limited. Business Reporter® is a registered trademark of Lyonsdown Ltd. VAT registration number: 830519543